Ai Weiwei: Introduction to Destruction

Inside the artist's exhibition at the Design Museum

For 8 years of my life, my days revolved around LEGO. The act of construction, using minuscule building materials to create entire cities, was thrilling for my 7-year-old self. As the years went on, I progressed from making simple set pieces to complex town halls and opera houses, organising pieces into their various colours and sizes before undertaking the task of assembling. This hobby revealed my inner God Complex - and I was the benevolent kind of creator who found it hard to tear my structures down and break my world apart.

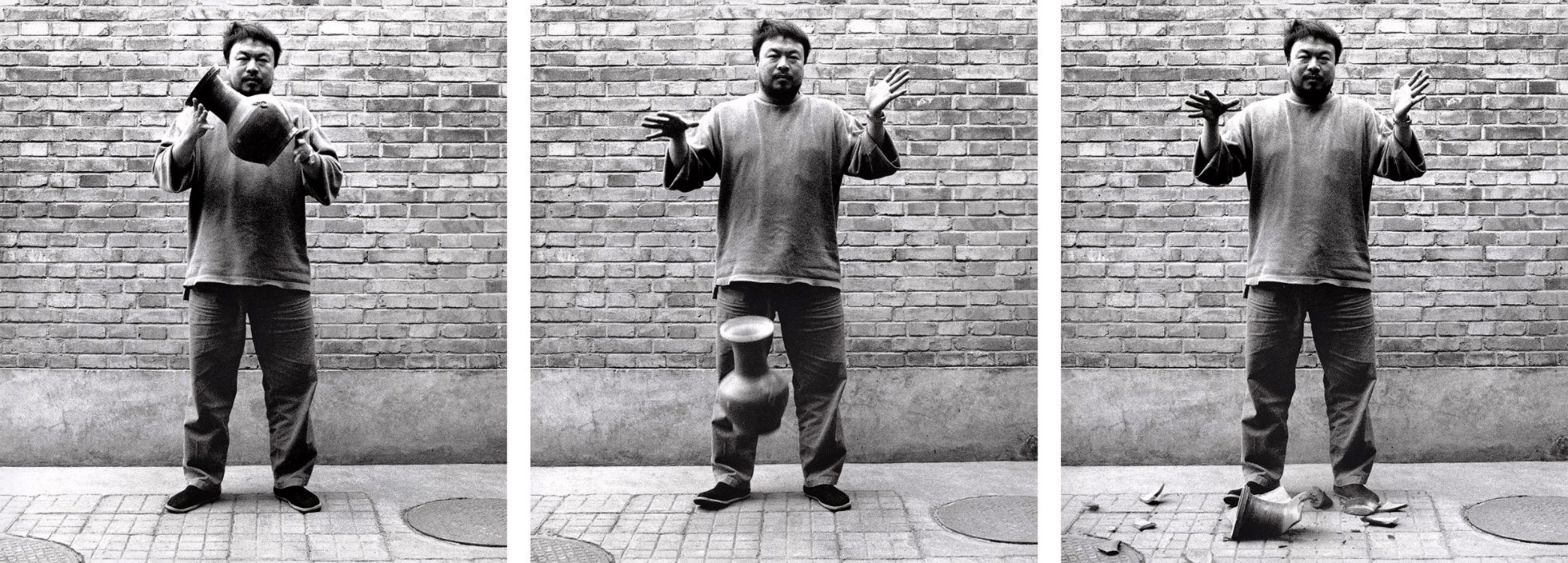

No such stranger to the act of destruction is the world-renowned artist Ai Weiwei, who infamously dropped an antique Han Dynasty Urn in 1955. In doing so, he was greatly criticised and labelled a vandal. But he also started conversations about why we destroy some things and not others - why we revere some things enough to put them in museums where other things get thrown in skips. Ultimately, he questions why we make things in the first place, from the tiniest of Lego bricks to huge Olympic stadiums.

Walking into Ai Weiwei’s new exhibition at the Design Museum ‘Making Sense’, I was met by ‘fields’ of objects that the artist has been collecting since the 1990s. One of these was UNTITLED (LEGO INCIDENT) (2014), an expansive and neatly squared-off lawn of Lego pieces. With hundereds of plastic bricks scattered on the floor, others still in bags and boxes, what stood out was a sense of disorder and destruction that culminated in, well, a pile of mess. With this piece, Weiwei is using the mass-produced, modular and speedily constructed nature of LEGO to comment on the carelessness of the construction industry in China. In LEGO, Weiwei sees an ‘objective kit that removes the trace of the artist’s hand and does not rely on his skill or taste’. The craft of making is reduced to a robotic process that leaves no trace of the human hands that built the structures – it is depersonalised.

This loss of the individual in the depersonalised world of mass construction is one of the central focuses in Weiwei’s work. The exhibition itself is rooted in the rapid urban development of China over the past 30 years. Through a wide assortment of sculptural installations, films, and photography, Weiwei, provides a commentary on the ever-evolving world of design, how it reflects the changing values of the societies we live in, and how we ultimately make sense of that evolution.

This allows space for rough and jagged Stone Age axe heads and knives (Still Life, 1993-2000), used to hunt and kill, to sit alongside delicately crafted Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) porcelain spouts that have been removed from their tea pots (Spouts, 2015). In placing these objects next to each other, we can see the move away from form and function towards beauty and aesthetics. We can see ‘material evidence of bygone civilisations, lost craft skills and forgotten cultural values’ ultimately indicating one of Weiwei’s most central themes: ‘the repression of the individual in modern China’.

Deconstruction takes on a whole new meaning, becoming a reflection on the people and governments who enact it. Due to the rapid urban expansion of China, entire regions were deconstructed and redeveloped en masse. In a series of videos and photographs, Weiwei documents these changes, recording the streets of a Beijing that no longer exist today, the fundamental structure of the city evolving beyond recognition to the artist (Beijing 2003 (2003), Beijing: The Second Ring (2005), Beijing: The Third Ring (2005)). It should be noted that, as someone who has designed and built his own complexes in Beijing and Shanghai, Weiwei has benefited from this redevelopment. However, the buildings themselves were ultimately destroyed by the state as punishment for his political activism.

Elsewhere, Weiwei makes a point of rebuilding from from destroyed matter: the sculpture Rebar and Case (2012) salvages the wood, marble and rebar from the rubble of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province that left 90,000 people dead, many of whom were children. Too many of these deaths were due to the collapsing of quickly built and cheaply made structures - the lack of care put into the act of making resulting in tragedy. The Backpack Snake (2008) and Life Vest Snake (2019) feature prominently on the wall in front of the exhibition entrance, and are bold reminders of the people most impacted by reckless acts of destruction. In using familiar, but ‘unremarkable objects’ that link to the refugee crisis and earthquake respectively, Weiwei forces viewers to confront the harsh reality faced by some of society's most disempowered and mistreated members.

This subversion of materials continues in the inverse giving of extreme value to ‘Ordinary Things’. Weiwei alongside traditional Chinese craftspeople has carved a Marble Takeout Box (2015), and a set of Marble Toilet Paper (2020) and Glass Toilet Paper (2022), as a commentary on the nature of luxury in waste and throwaway culture. In elevating these disposable objects into art made by extremely skilled craftspeople, Weiwei moves away from the cheaply made and mass produced and asks us to consider and respect the act of making.

By changing the meaning of the object, shaking its foundations, we are also changing our own condition. We can question what we are.

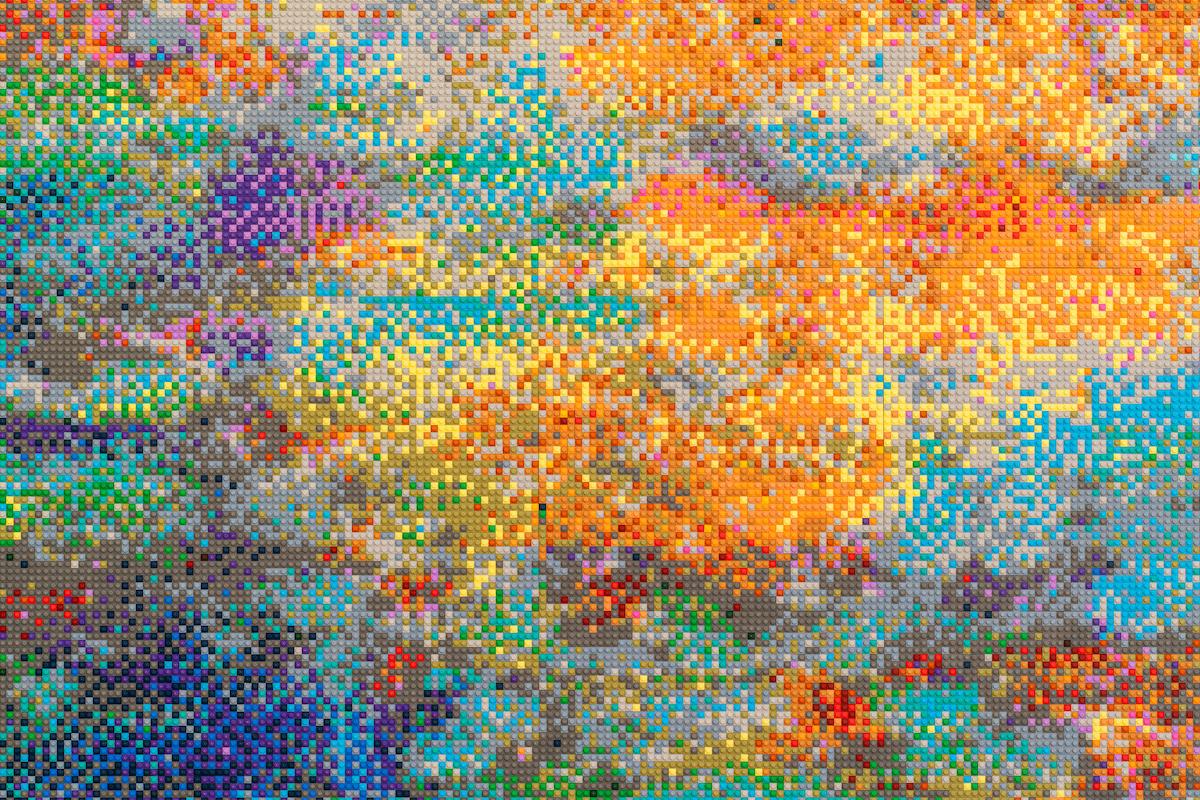

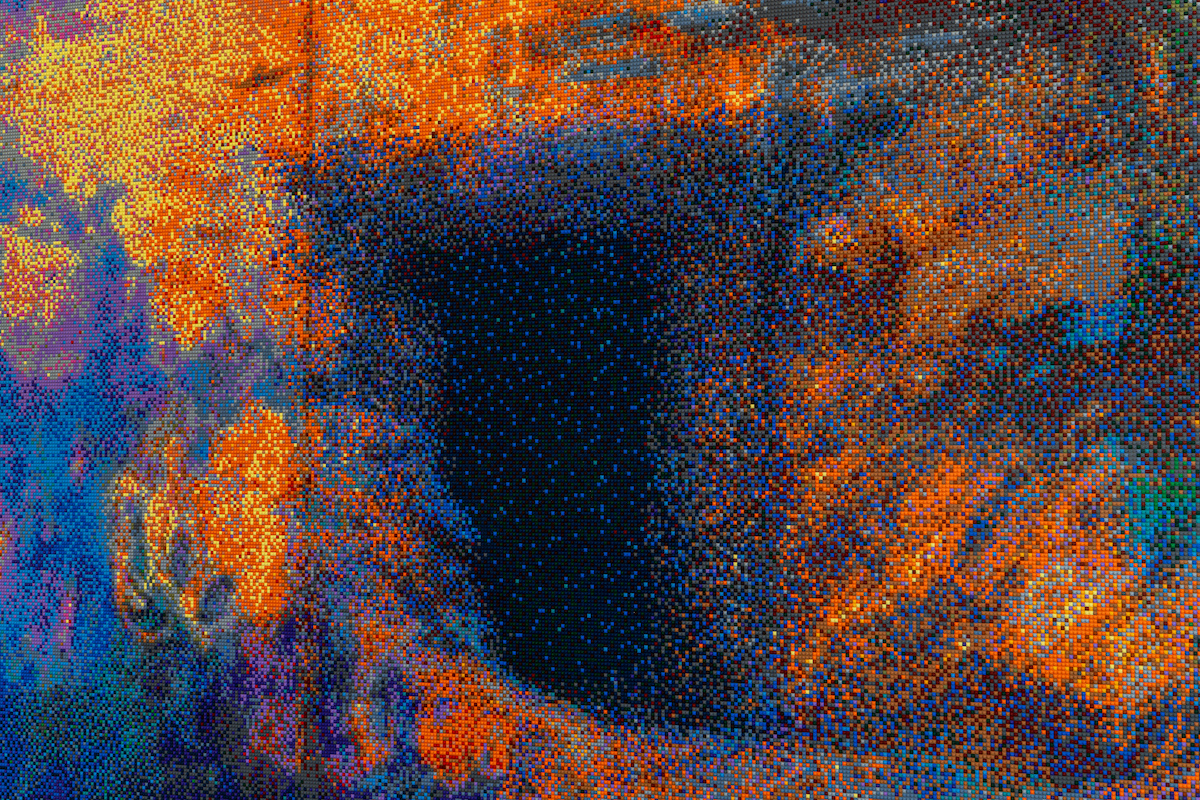

The culmination of this study lies obscured behind wooden columns of a temple from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 CE) that have been formed into a complex architectural structure alongside tables of the same period, the ruined deconstruction taking on an entirely new form in Through (2007-8). Through the columns, bold burst of colour can be seen and almost like an optical illusion, Water Lilies #1 (2022) emerges.

This piece is the largest LEGO work that Weiwei has created and takes inspiration from the idyllic scene of the famous painting by French impressionist Claude Monet. A far cry from his 2014 LEGO Incident this piece features 22 colours of around 650,000 meticulously placed LEGO tiles and is over 15 metres in length.

The installation still carries over the theme of impersonal creation, with Monet’s brush strokes being recreated as pixel-like blocks. Yet one cannot help but think of the hands that placed those pieces – the time and care that went into its construction. There is value given to the piece and by extension to the LEGO bricks, not only due to its similarity to Monet’s work, but due to the nature of it being exhibited. But amongst that, there is the artist’s personal addition – a dark portal on the right side of the piece, disrupting the picturesque landscape. It symbolises the door to the underground home where Weiwei and his father lived in forced exile in the 1960s, punctuating that sense of deconstruction of self, home and reality. It is a powerful and impactful image to place amongst a beautiful work of art. But of course, ultimately, its beauty and value are all impermanent, and can be ripped apart into tiny pieces by a pair of hands and some force, not unlike that dropped Han Dynasty Urn.

Tickets for the exhibition ‘Ai Weiwei: Making Sense’ at the Design Museum are available to buy until 30 July 2023.

By Elise Nwokedi